Authors: Andreas Eberhard-Ruiz and Kevwe Pela, Jobs Group, World Bank.

In this blog, we explore whether the process of structural change differs between resource-rich and resource-poor economies, and discuss the implications of our findings for jobs strategies in resource-rich countries.

The ‘Great Convergence’ of global incomes seen over the last 30 years, was triggered by an unprecedented acceleration in the rates of growth and structural change in China, India, and East Asian countries. Most Low-Income Countries (LICs) did not experience such rapid transformation. But, as Asia’s boom drove up commodity prices, many resource-rich developing countries benefited from growth, through exports of minerals and other natural resources. However, our analysis shows that resource-rich countries grew more slowly and created fewer waged jobs.

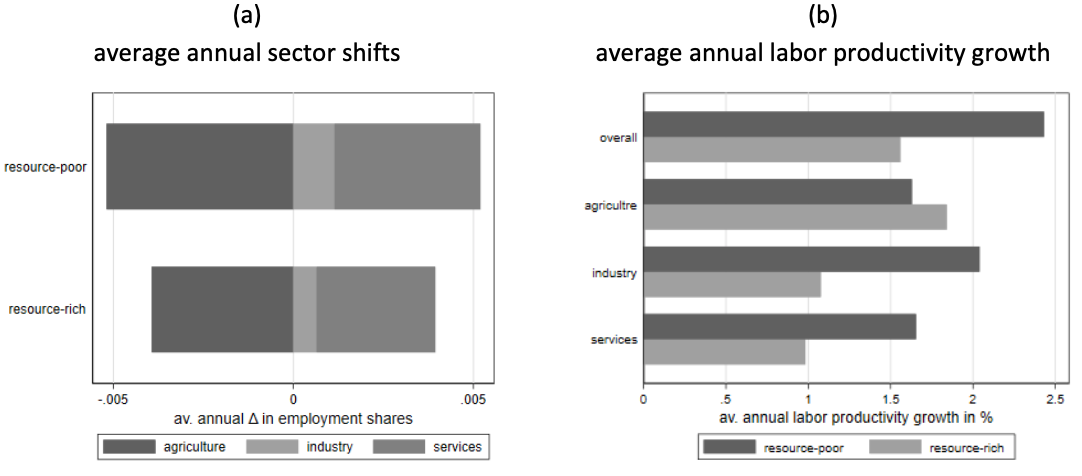

Chart 1 analyzes changes in economic structures over five-year intervals between 1991 and 2016, using data for 53 resource-poor and 20 resource-rich LICs. Chart 1 (a) shows that structural change, measured in terms of sectoral employment shifts from lower productivity agriculture into higher productivity services and industry, was positive in both resource-rich and resource-poor countries, but was lower in the resource-rich.

A lower rate of structural change does not necessarily imply lower overall productivity growth in resource-rich countries. Resource-rich countries tend to have highly capitalized enclave mining and extraction industries. According to our data, the average productivity gains of moving one person from agriculture into industry are 30 percent higher in resource-rich than in resource-poor LICs. This would imply that resource-rich countries can afford to have lower movement from agriculture into industry without negatively affecting overall productivity growth.

Yet the real challenge lies with services because productivity gains of shifting people from agriculture into services is about 20 percent lower in resource-rich than it is in resource-poor countries. Since most structural change in resource-rich countries comes from employment shifts into services, overall productivity gains from structural change are likely to be smaller in resource-rich countries. Chart 1 (b) confirms this. Average labor productivity growth in the resource-poor countries was faster than in resource-rich countries. Moreover, average productivity growth within sectors was almost twice as high among LICs with limited natural resources than among those with natural resources. It is therefore unsurprising that annual per capita GDP growth was 2.7 percent in resource-poor LICs and only 1.7 percent in resource-rich LICs.

Chart 1: The patterns structural change in resource-poor and resource-rich countries

Notes: Figure reports annual changes in sector shifts (panel a) and labor productivity growth (panel b) for 73 LIC over five-year intervals between 1991 and 2016.

The finding that economic growth tends to be lower in resource-rich LICs is not new. There is a vast literature pointing to the dilemma countries face when trying to leverage natural resources to accelerate their economic development. Natural resource-driven growth exposes countries to boom and bust cycles resulting in increased volatility, which can lead to lower rates of investment and procyclical government spending. Dutch disease effects may kick in through an increase in the relative price of non-tradeable to tradeable goods. This can negatively affect countries’ external competitiveness and can depress non-resource exports. Furthermore, the overall quality of institutions and governance may suffer due to an increase in rent-seeking behavior and increased corruption. Each of these can limit economic transformation and thwart labor productivity gains for workers, who in LICs, tend to be in tradeable agriculture, or dependent on agricultural commodity processing for their cash incomes.

What the cross-tabulations in chart 1 are not able to tell us, however, is whether beyond the challenges of overcoming the natural resource curse, there is something inherently different to the process of structural change in resource-rich economies that slows the creation of better-quality jobs and reduces the transformative impact of structural change on people’s lives. Our data confirms that on average, resource-rich LICs created less opportunities for waged employment than resource-poor LICs between 1991 and 2016. Yet, this may simply be driven by the fact that overall GDP and productivity growth were lower in resource-rich LICs. More interesting is thus the question of whether resource-rich and resource-poor countries that experienced similar levels of productivity growth also generated the same opportunities for waged employment, which as we saw in blog #5 is a key pathway to better-quality jobs.

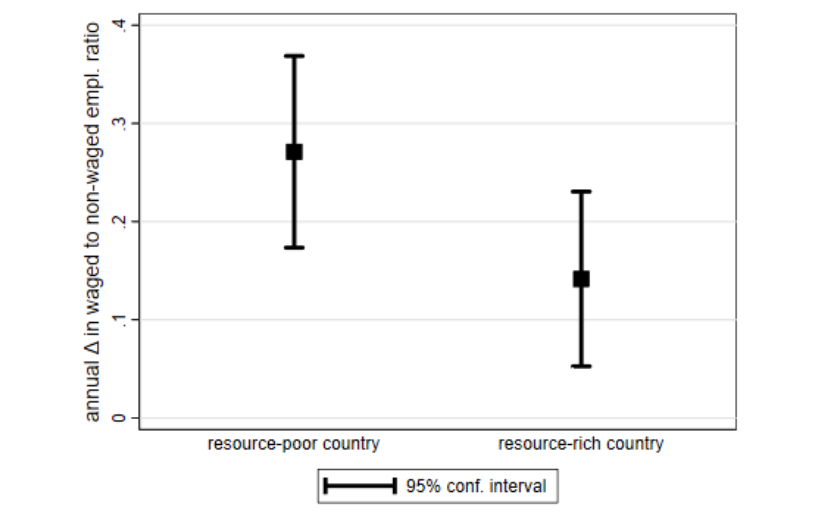

Building on the same regression framework used in blog #7, we compare how average labor productivity growth correlates with the waged to non-waged employment ratio, depending on whether a country is resource-rich or resource-poor. Chart 2 shows the results of this regression analysis. If a resource-poor and a resource-rich country were to experience the same productivity growth of 1% per annum, the resource-poor country would create more waged employment. The waged to non-waged employment ratio would rise by 0.27 points in the resource-poor country and by 0.14 points in the resource-rich country. Put differently, our results suggest that resource-rich LICs require twice as much productivity growth as resource-poor LICs to generate the same increase in the waged-to-non-waged employment ratio.

Chart 2: Estimated increase in the waged to non-waged employment ratio on account of an assumed 1%-point increase in average labor productivity growth

Notes: Results are based on a regression analysis examining changes in the waged to non-waged employment ratio using data for 73 LICs over five-year intervals between 1991 and 2016 with country-fixed effects and controls for initial sector employment shares, initial waged to non-wage employment ratio and initial log p.c. GDP.

How can we explain this difference, and what does it mean for jobs strategies in resource-rich countries? The first thing one should note is that the extraction of natural resources tends to be very highly capital-intensive, and is becoming more so, as new sources of oil and minerals are harder to find. Economies with expanding natural resource sectors can therefore be expected to experience strong increases in average labor productivity, in which new drilling machines are deployed, but where the number of additional waged jobs created is limited. Capital-intensity means that labor is more productive on average in mineral-rich sectors, but more capital-intense production does not necessarily generate additional employment. For instance, by 2015, Ghana’s oil and gas industry had only created about 7,000 direct jobs after oil was discovered in 2007 – an almost negligible number compared to Ghana’s population of 28 million people. The same is true for Uganda, for which the nascent oil and gas sector is projected to stabilize at about 3,000 direct jobs, once the initial construction and development phase currently underway is completed.

The jobs challenge in natural resource-rich countries is therefore particularly steep. Resource-rich economies do not only tend to grow more slowly, but also create fewer waged jobs as they grow. Job strategies in natural resource-rich countries therefore need to put special emphasis on how to overcome these challenges. One possibility is to focus on strengthening sectoral links with the more labor-intensive sectors of the economy and to boost productivity growth in the services sector. More on that in a future blog – stay tuned!