Author: Dino Merotto, Jobs Group, World Bank.

Blog #1 in our series showed that growth in labor productivity explains the differences in per capita income growth across countries. When we break down labor productivity growth into within and between sector components, we see that the reallocation of labor from lower productivity agriculture to higher productivity industry and services makes a significant contribution to growth in Low Income Countries (LICs). Reallocation contributes more when it comes with growth in waged employment.

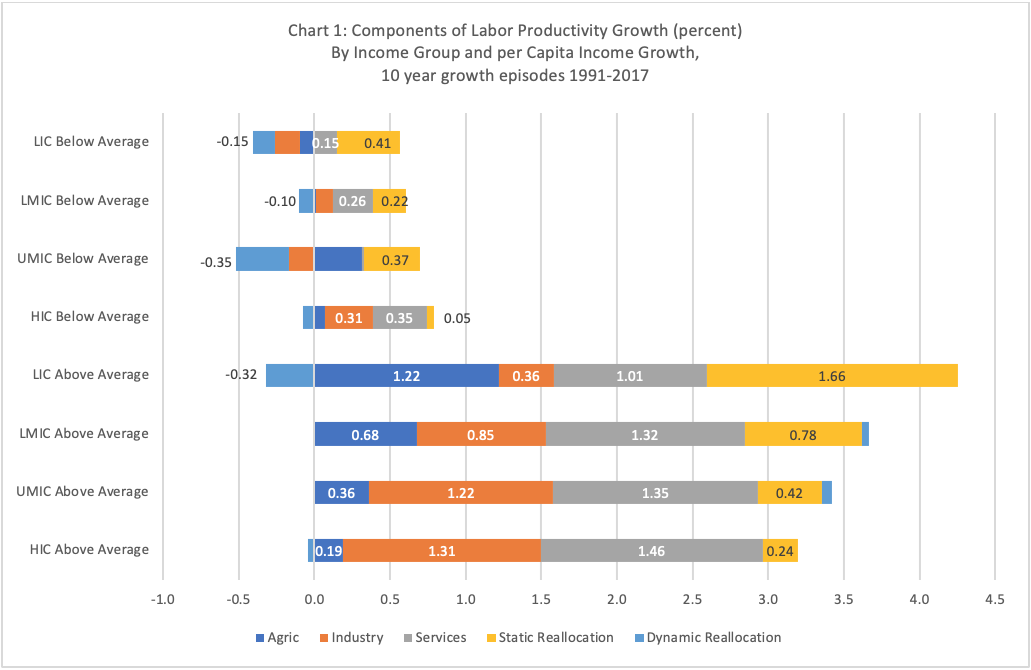

Chart 1 shows the results for 2,500 growth episodes of 10 years’ duration from 163 countries over the period 1991-2017. The periods are arranged in income groups, and by whether per capita income growth in each group is above or below the global average of per capita income growth.

Aggregate labor productivity growth is broken down into 5 components. Three of these components refer to growth in average sectoral labor productivity within agriculture, industry and services, and two components arise from the reallocation of workers from one sector to another. The reallocation – or movement of labor between sectors – has a “static” and a “dynamic” element. The static element is positive (negative) when labor moves from lower (higher) to higher (lower) productivity work. The dynamic element is positive (negative) when the average labor productivity of the receiving sector is rising (falling) as labor moves in.

A negative dynamic effect isn’t always a bad thing. But it can be. It would be okay in a labor abundant economy for instance, if the negative dynamic component resulted from investment in the production of new, more labor-intensive products like garment manufactures. More typically in LICs though, a negative dynamic component is a signal that the shift involves the creation of lower productivity, lower capital-intensity jobs.

Chart 1 shows five things about labor productivity growth.

- First, consistent with Blog #1 in this series, faster growth in per capita income comes with faster growth in labor productivity;

- Second, in episodes of faster growth in per capita income in LICs and LMICs, there was a significant contribution to labor productivity from static reallocation (the movement of labor out of agriculture). For above average growth in LICs and LMICs, static reallocation added 1.7 and 0.8 percentage points to average annual labor productivity growth. Gains from labor reallocation in faster growth periods in LICs and LMICs exceeds the contribution made by labor productivity improvements within agriculture.

- Third, the contribution to growth from labor reallocation and growth in agricultural productivity seem to be correlated in faster growing growth episodes, but not when growth is below average.

- Fourth, in LICs and in all income groups when there is slower than average growth, the contribution of dynamic reallocation to labor productivity was negative.

- Fifth, the contribution to labor productivity growth when there is above average growth; (i) declines for agriculture, (ii) increases for industry, and (iii) increases slightly for services, but is almost equal across country income groups. There is no such pattern in countries that are growing below average in per capita income.

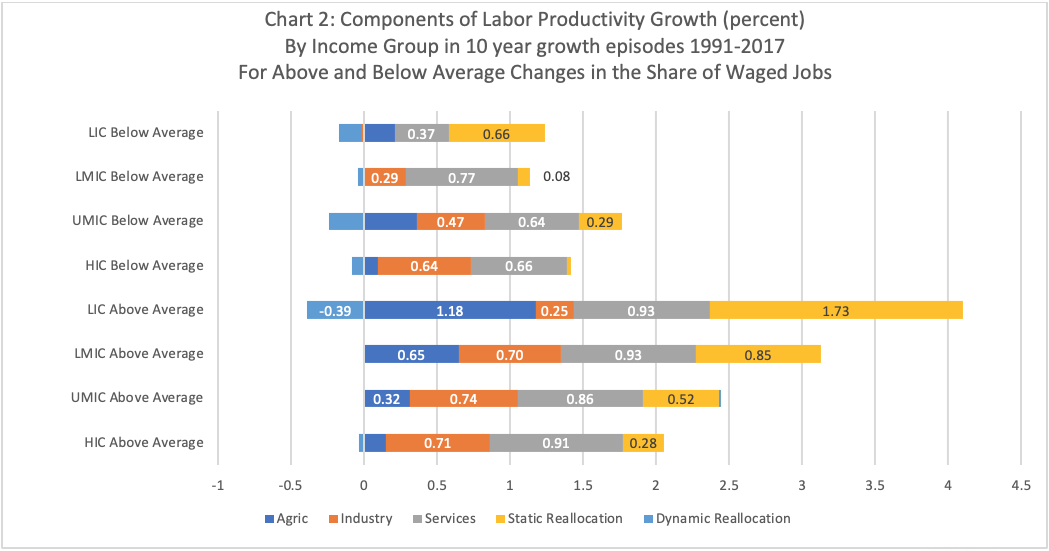

Chart 2 uses the same data from 10-year growth episodes to show the decomposition of labor productivity growth when the share of waged employment increases by more and less than the average. The pattern is quite similar, but compared to chart 1, the contribution of static reallocation to average labor productivity is higher when the waged share increases faster. This is particularly true in LICs and LMICs. That productivity growth is higher when more waged jobs are being created is consistent with some of the oldest observations in economics. Division of labor and economies of scale are made possible when workers come together to work in firms that augment their labor with capital. In blogs #5 and #6, we will look in greater detail at how employment type changes by per capita income, and how increases in waged employment help reduce poverty. We discuss both human and physical capital accumulation later in the series.