Photo credit: Scott Wallace / World Bank

Authors: Kevin Donovan, Will Jianyu Lu, and Todd Schoellman

Economic development requires the reallocation of workers to more productive occupations, sectors, and regions. As such, evidence on labor market dynamics is critical for understanding whether labor markets are enabling the necessary movements of workers.

In our recent research, we provide new evidence on dynamics by building a dataset consisting of short rotating panel labor force surveys in 45 countries with GDP per capita ranging from below $5,000 (India, Nicaragua, Philippines) to more than $50,000 (USA, most of Europe). The final dataset covers 74 million workers each tracked for two or three consecutive quarters. We use the database to study how workers in these many countries transition among labor market statuses.

Aggregate measures of labor market turnover are higher in poor countries

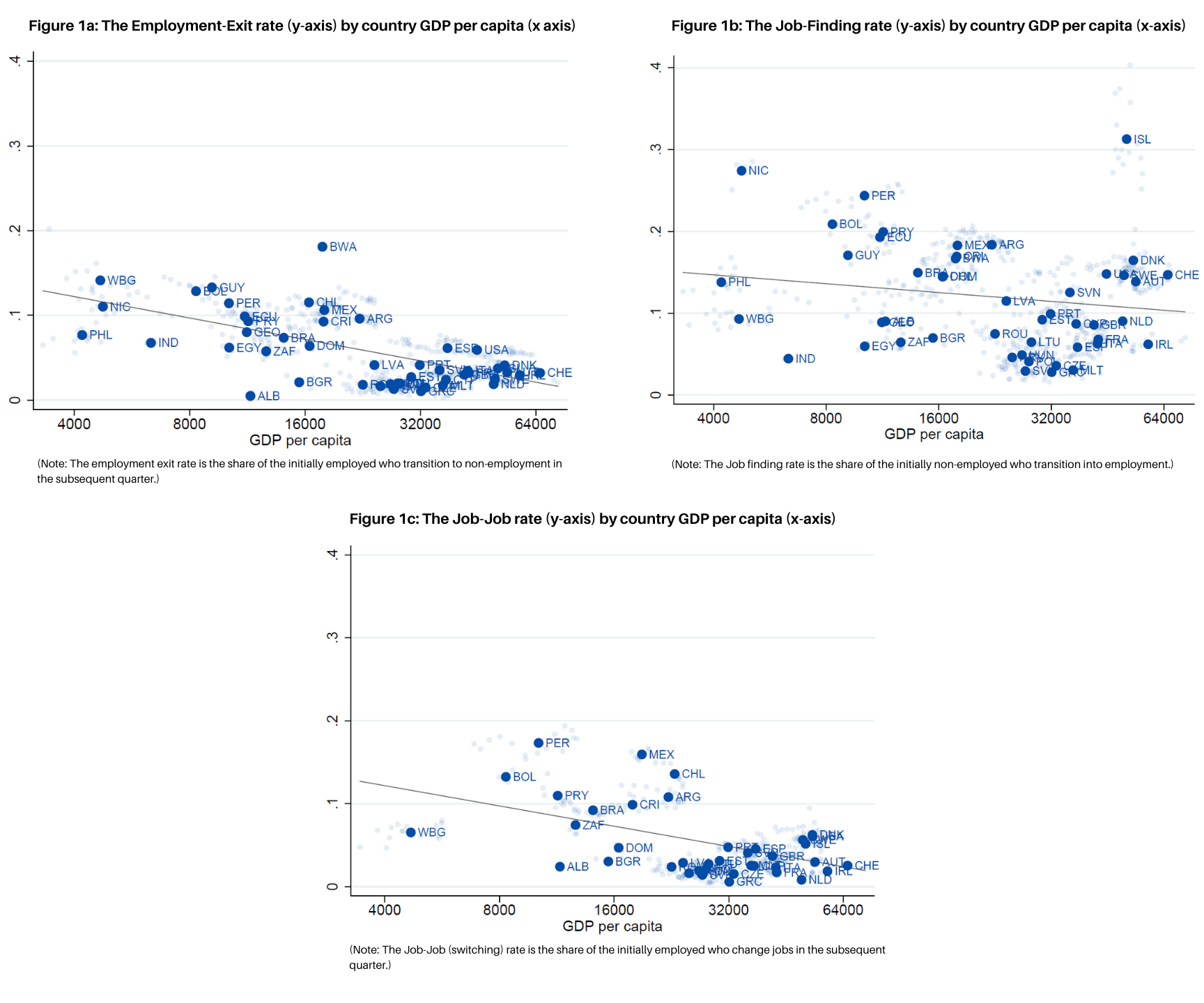

Our first step is to reassess the relationship between GDP per capita, labor market flows, and labor market regulations, which has been studied intensively mostly among rich countries. We focus on three key moments: the job finding rate (non-employment to employment), the job exit rate (employment to non-employment), and job switching rate (flows from one job to another). We find that all three are negatively correlated with GDP per capita and that accounting for labor market regulations does not change this fact.

What drives these negative relationships? One possibility is that they reflect workers making the necessary reallocation towards better jobs in productive sectors in developing countries. Instead, our results suggest a different story: most of the turnover we observe is “churn” between self-employment, low-earning wage jobs, and non-employment. That is, it is not workers climbing the job ladder.

What drives these negative relationships? One possibility is that they reflect workers making the necessary reallocation towards better jobs in productive sectors in developing countries. Instead, our results suggest a different story: most of the turnover we observe is “churn” between self-employment, low-earning wage jobs, and non-employment. That is, it is not workers climbing the job ladder.

Evidence: Turnover is mostly driven by self-employment and low-earning wage jobs

Our evidence for this comes in two steps. First, we consider the impact of self-employment, which is well-known to be more common in developing countries. We find that flows into self-employment account for all of the aggregate relationship between the job-finding rate and development and a large share of the aggregate relationship between the employment exit rate and development.

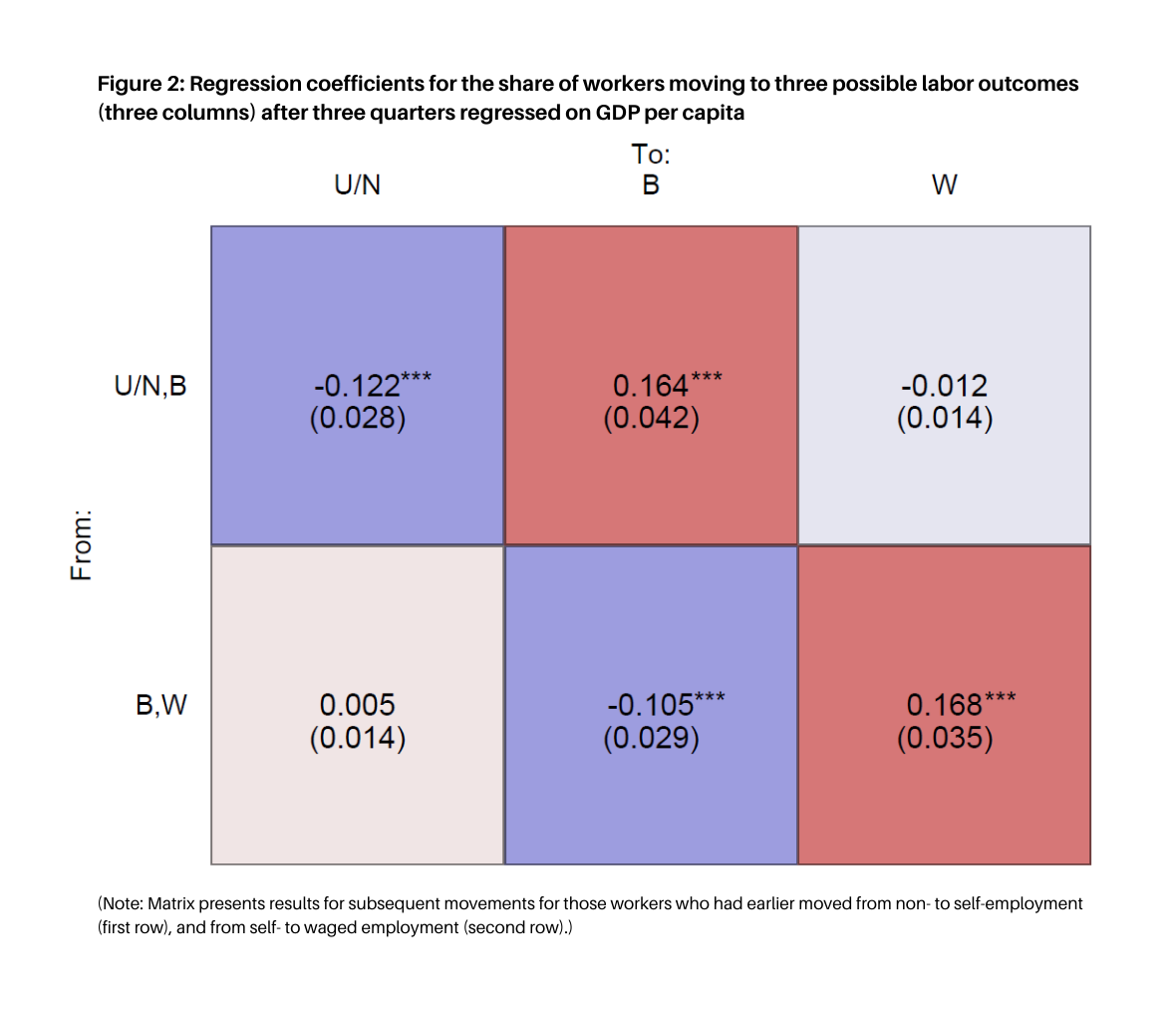

But what is self-employment? Is it a steppingstone to better wage jobs? Or is it better represented as disguised unemployment or subsistence entrepreneurship? Our evidence points to the latter. In 26 of our 45 countries, we can track workers for three consecutive quarters. We use these countries to ask what happens to workers who enter self-employment or who move from self-employment to wage work. The figure below shows the results.

The first row shows what happens to workers who move from non-employment (U/N) to self-employment (B). They can return to non-employment, remain self-employed, or move up to wage work (W) in the third quarter. The coefficients are the result from regressing the share of workers making that move on (log) GDP per capita, so positive numbers (shaded in red) indicate transitions that are more common in richer countries, while negative numbers (shaded in blue) indicate transitions that are more common in poorer countries. Workers who find self-employment in developing countries are much more likely to return to non-employment just one quarter later.

The first row shows what happens to workers who move from non-employment (U/N) to self-employment (B). They can return to non-employment, remain self-employed, or move up to wage work (W) in the third quarter. The coefficients are the result from regressing the share of workers making that move on (log) GDP per capita, so positive numbers (shaded in red) indicate transitions that are more common in richer countries, while negative numbers (shaded in blue) indicate transitions that are more common in poorer countries. Workers who find self-employment in developing countries are much more likely to return to non-employment just one quarter later.

The second row shows what happens to workers who move from self-employment to wage work. The main result here is that they are more likely to return back to self-employment just one quarter later and less likely to persist in wage work.

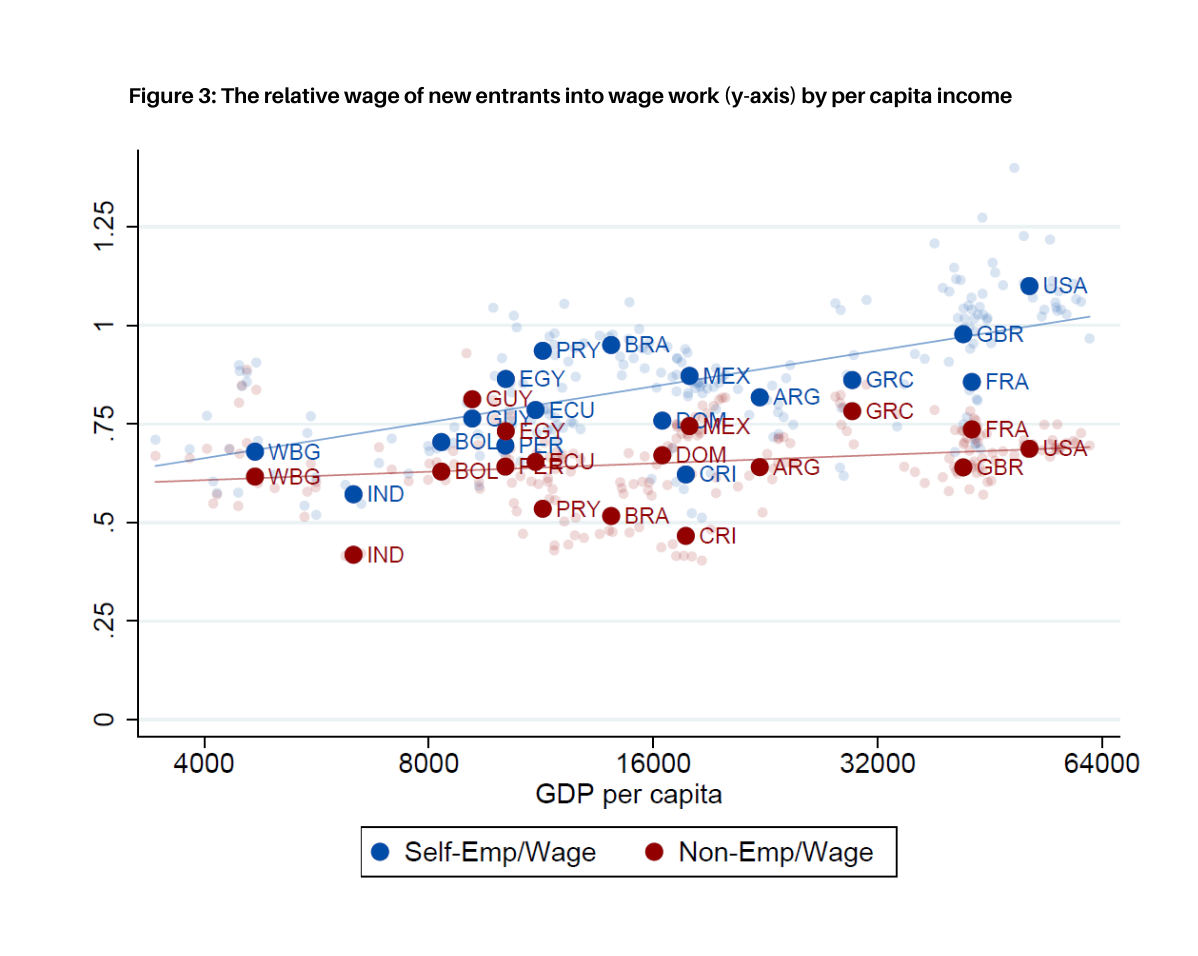

Workers who move from self-employment to wage work in developing countries also earn low wages. The next figure compares the wages of workers who were previously self-employed to the wages of workers who were previously non-employed. In rich countries, self-employment leads to higher wage work, while in developing countries self-employment and non-employment both lead to lower-wage work. Altogether, self-employment in developing countries does not appear to be a steppingstone to better jobs.

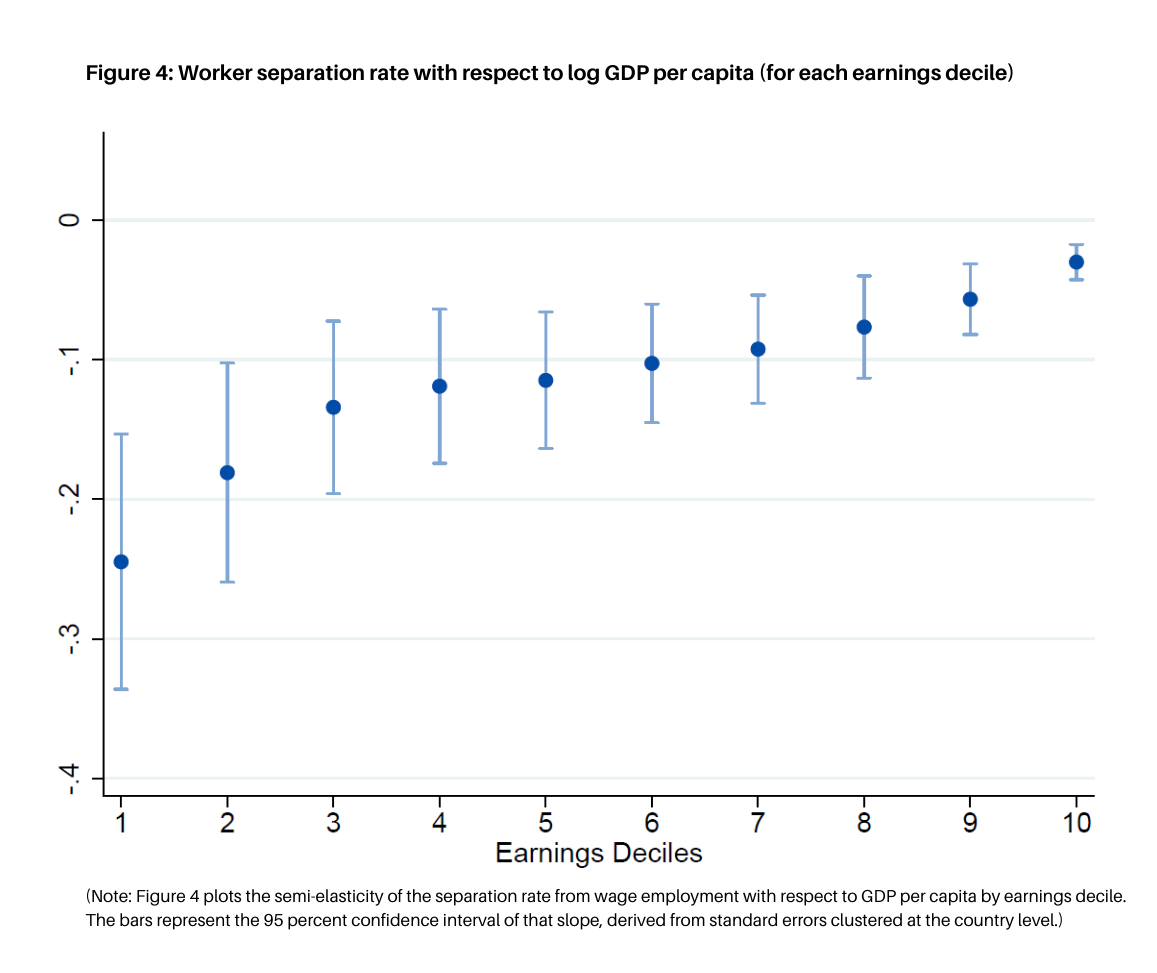

Workers are also more likely to separate from (but not find) wage work in developing countries. We find that this is mostly accounted for by workers in low-earnings jobs. For example, workers in the top earnings decile in Denmark separate at a rate of 6 percent quarter, which is not too different from the 10 percent rate in Peru. But in the bottom earnings decile the figure for Denmark is 20 percent, while for Peru it is 63 percent. Alternatively, the lowest earners in Denmark separate at the same rate as those in the eighth earnings decile in Peru. This result holds more broadly. The next figure shows the semi-elasticity of the separation rate with respect to GDP per capita, computed separately for each earnings decile.

Workers are also more likely to separate from (but not find) wage work in developing countries. We find that this is mostly accounted for by workers in low-earnings jobs. For example, workers in the top earnings decile in Denmark separate at a rate of 6 percent quarter, which is not too different from the 10 percent rate in Peru. But in the bottom earnings decile the figure for Denmark is 20 percent, while for Peru it is 63 percent. Alternatively, the lowest earners in Denmark separate at the same rate as those in the eighth earnings decile in Peru. This result holds more broadly. The next figure shows the semi-elasticity of the separation rate with respect to GDP per capita, computed separately for each earnings decile.

The separation rate is more strongly negatively correlated with development for lower earnings deciles. The correlation is approximately 5 times stronger for the lowest earnings decile than the highest.

The separation rate is more strongly negatively correlated with development for lower earnings deciles. The correlation is approximately 5 times stronger for the lowest earnings decile than the highest.

Putting it all together: Poverty and Turnover

When we combine all of this evidence, we come to the conclusion that the aggregate turnover we observe is primarily a consequence of poverty, in that it depends on (1) the differential role of self-employment and (2) the set of low-earnings jobs available in low and middle income countries. We use accounting decompositions to show that these low-earnings, high-turnover jobs employ young workers with low levels of education and less skilled occupations. That is, the results are driven by exactly the types of jobs and workers that are more prevalent in developing countries.

While our work stops short of any explicit policy recommendations, it suggests fruitful margins on which to focus. Developing better and more stable wage jobs – via education policy or industrial shifts – may help lower turnover. This lower turnover may have important implications for on-the-job-training and other forms of human capital accumulation that benefit from stable employment relationships. While understanding such links requires more detailed data, we hope our results can provide a motivating guide for such work in the future.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Central Bank of Chile, its Board members, the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, the Federal Reserve System, or the data providers.