Author: Andreas Eberhard-Ruiz, Jobs Group, World Bank.

Between 1996 and 2003, Nigeria’s per capita GDP grew by almost 3 percent per annum and the proportion of people living under US$ 1.90 per day – the World Bank’s threshold to measure extreme poverty – fell from 64 percent to 54 percent. By contrast, poverty did not decline at all in the following six years, despite an acceleration in per capita GDP growth to over 4 percent per annum. Similarly, in the first and second half of the 1990s, Bangladesh grew by about 2.5 percent annually on a per capita basis. But whereas poverty declined by almost 10 percent points in the first half of the decade, it hardly declined during the second.

These examples confirm a well-known fact. Whereas economic growth reduces poverty, it is not growth alone that matters for poverty reduction. Many other factors can preclude the most vulnerable in developing countries from participating in growth. For instance, nutrition programs and access to basic services in education and health are crucial to making growth broad and inclusive in the long-run. Social safety nets insure poorer households against economic volatility and negative income shocks. Cash transfers are often essential to allow the very poorest households to break free from poverty traps.

Many policy makers and practitioners also believe that an economy’s ability to generate better jobs for its people is equally important to reduce poverty. Yet, the relationship between growth, better jobs, and poverty alleviation is arduous to unpack. In most developing countries, household surveys – on which poverty estimates rely – are only conducted periodically, and countries and their surveys differ in many dimensions, which make comparisons across countries challenging. However, we are now starting to compile enough data points to compare jobs outcomes with poverty estimates in growth episodes within countries over time.

A recent regression analysis exploits within-country variation in the data for 1200 growth episodes across 145 countries. It presents striking findings. At low levels of income, an increase in the share of population in waged employment appears to be a more important driver of poverty reduction than per capita growth per-se. Yet while growth remains important for poverty reduction at higher levels of income, the role of waged jobs diminishes as economies get richer.

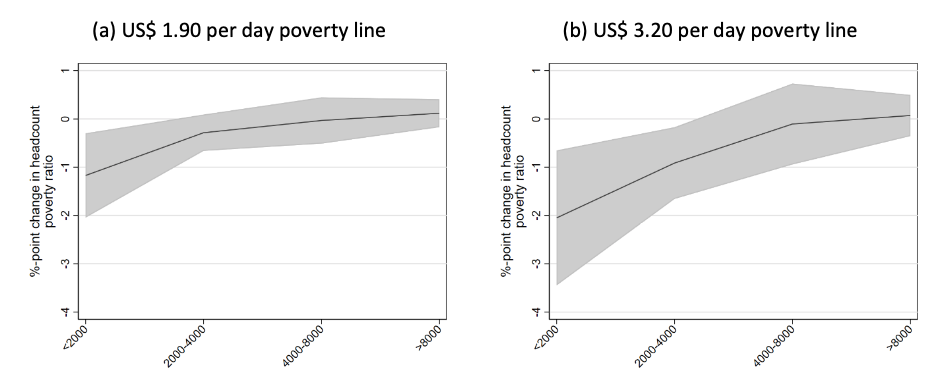

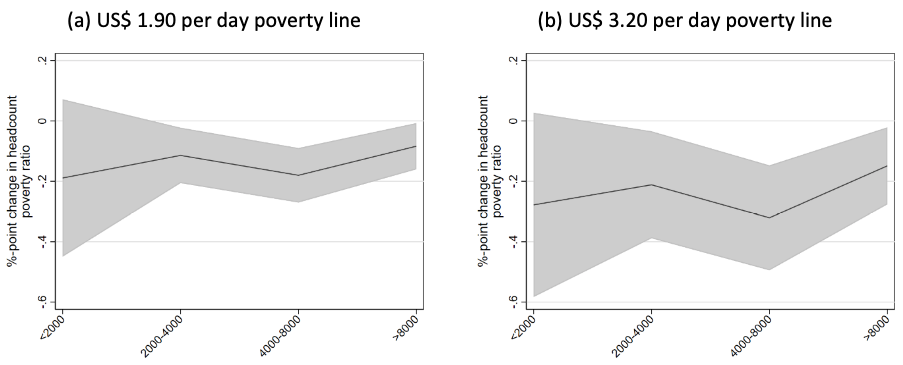

The regression results are illustrated in charts 1 and 2. For per capita GDP levels of less than US$ 2000, a 1-percentage point increase in the population share in waged employment is associated with a 1-percentage point reduction in the poverty rate when using the US$ 1.90 poverty line, and a 2-percentage point reduction when using a poverty line of US$ 3.20. This correlation disappears at higher income levels. Meanwhile, the impact of a 1 percentage point increase in per capita GDP growth reduces poverty by 0.1 to 0.2 percentage points for the US$ 1.90 poverty line, and 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points for the US$ 3.20 poverty line regardless of a country’s income level.

Blog #5 in this series showed that waged jobs provide a progressively higher share of employment for LMICs than for LICs. This analysis of growth episodes adds the dimension of change over time to the analysis and confirms that an increase in the availability of waged jobs needs to take center stage in inclusive growth strategies and in the fight against extreme poverty in LICs.

Our next blog will examine how economies that create increases in the share of waged jobs generation typically grow. Blog # 11 will analyze the transformational effect of waged jobs at household level.

Stay tuned!

Chart 1: Impact of an increase in waged employment on headcount poverty rates for different income levels

Notes: Figure depicts the predicted impact of a 1 percentage point increase in the number of paid employees relative to the total population for different per capita GDP levels. Results based on regression analysis of 1192 growth episodes across 145 countries with country-fixed effects and controls for per capita GDP growth, initial per capita GDP level, initial population share in waged employment, initial poverty rate, initial population size, and episode length. Grey shaded area equals 95% confidence intervals alllowing for clustering at the country level.

Chart 2: Impact of an increase in per capita GDP growth on headcount poverty rates for different income levels

Notes: Figure depicts the predicted impact of a 1 percentage point increase in the per capita GDP growth rates for different per capita GDP levels. Results based on regression analysis of 1192 growth episodes across 145 countries with country-fixed effects and controls for change in population share in waged employment, initial per capita GDP level, initial population share in waged employment, initial poverty rate, initial population size, and episode length. Grey shaded area equals 95% confidence intervals alllowing for clustering at the country level.